Once again, we find ourselves at a Wikipedia stub page for a woman in music, for composer Jessie Furze. Though there’s a pretty sizeable collection of works listed, there’s not much in the way of biography. Jessie was once again a composer and pianist, and dedicated much of her career to writing educational music. But a quick look in the BNA lands us straight with Jessie in Norwood, for a while now I’ve been bumping up against the musical world of the London suburb – with Streatham not far behind. This is about as much intrigue as I need to lure me into finding more information out about these amazing women, so if you fancy a ride into newspaper lane, jump in.

Continue reading “Following threads of women composers: Jessie Furze”Category: Research Writings

Following threads of women composers: Harriet Maitland Young

As should by this point be becoming clearer, I like a wild goose chase. In this case, a very short Wikipedia article on Harriet Maitland Young (1838-1923) got my attention, a composer about whom very little is known other than her mention in the Women’s Work in Music (1903). The Wikipedia article lists four operettas by Young, and notes she is buried in Camden. So if we dig a bit more… what do we find? I think you’ll know by now I can’t resist a mystery adventure.

Continue reading “Following threads of women composers: Harriet Maitland Young”Avril Coleridge-Taylor and the Royal Albert Hall

This summer Avril Coleridge-Taylor’s music will be played at the Proms for only the second time, with her piece ‘The Shepherd’ receiving its debut as part of the Great British Works Prom on the 4th August. She is a recent Proms arrival, her orchestral work ‘A Sussex Landscape’ was first performed there only last year. Yet despite this long neglect of her output, Avril was no stranger to the Albert Hall as a venue for her own work (and yes, the Proms only moved to the RAH in 1941). The Coleridge-Taylor family had a special connection with the concert hall.

Continue reading “Avril Coleridge-Taylor and the Royal Albert Hall”Eva Jessye

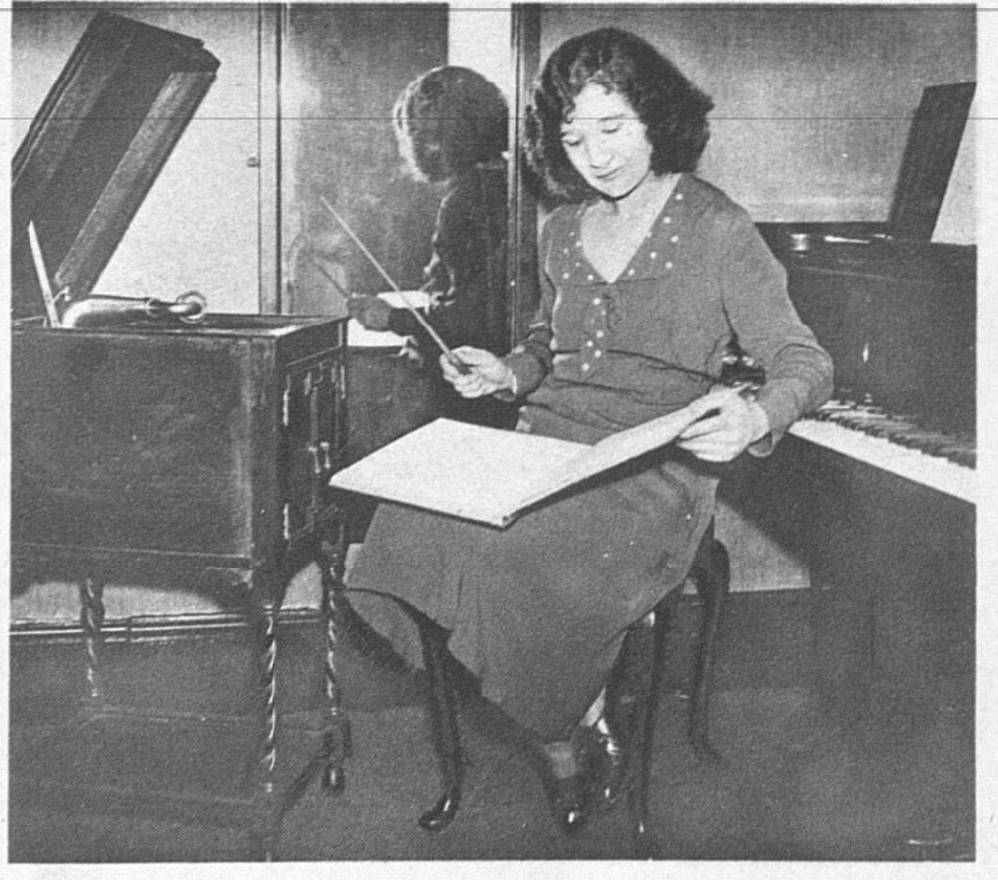

(b. 1895, Coffeyville, Kansas – 1992)

Choir director, music director, activist, composer, journalist. Led the official choir of the March on Washington (1963)

Jessye’s musical leadership during the 1920s and 1930s placed her at the helm of some of the most important significant productions during this period, on Broadway and in Hollywood. She was a music director for King Vidor’s Hallelujah (1929), the first Black cast sound film (though Vidor was white), and her choir, the Dixie Jubilee Singers appeared in the film. She was accepted to university aged 14, because she wasn’t allowed to enroll in high school education as a Black woman. She met and was inspired by Will Marion Cook, and after graduation worked as a high school teacher. In this article I’ve found some of her remarks in interviews and coverage of her work.

Continue reading “Eva Jessye”Part 6: The Megamusical and Whiteness

So this perhaps the most tricksy part of all of this – how do we know that this musical engages with whiteness? Part of the answer is because it doesn’t engage with anything else. To be unconcerned with race in the autumn of 1985 is a luxury only whiteness could allow; being indifferent is a privilege only whiteness would embrace.

Continue reading “Part 6: The Megamusical and Whiteness”Part 5: Les Mis, white optimism, and Autumn 1985

The musical as a form relies on a relatively straightforward dramaturgical structure, broadly used in the majority of musicals, where a set number of characters, usually relatively small in number, go through some kind of conflict or experience and their story is resolved by the end of the show, ideally with some kind of happy ending. The happy ending in Les Mis might be fairly thin on the ground, but there is some kind of hopefulness. In this part I’m going to explore how the musical is structured, and consider what does this have to do with Autumn 1985, and narrative whiteness?

Continue reading “Part 5: Les Mis, white optimism, and Autumn 1985”Part 4 – Staging revolution in Handsworth Songs

Handsworth Songs opens with an image of a Black security guard looking at a large engine (perhaps in a museum), intercutting with a series of unsettling images and sirens (birds roosting, a rotating clown face), before settling on the civic centre of Birmingham and the statues of the ‘great noble men of Birmingham’ outside the city’s library buildings. Images of the morning after street protests are intercut with the same clown; then Home Secretary Douglas Hurd visiting the residents of Birmingham. (Hurd had to leave the area quickly after his arrival, news footage records his unwelcome visit).

In one of the most distressing sequences of Handsworth Songs, which comes only minutes in, a young Black teenager is chased by police, we seem him violently restrained as other young Black people look on – watching but not surprised by what they are seeing. The film then moves into a series of archival footage of earlier Caribbean immigrants to the UK, of hopeful wedding photos and ballroom dancing. Homi Bhabha argues that Handsworth Songs resists time because it stages ‘the historic present of the riots’[i], it explicitly presents fractured time:

Continue reading “Part 4 – Staging revolution in Handsworth Songs”Part 2 – Rehearsals and Riots, a chronology

Les Misérables was in rehearsals when the so called Handsworth Riots took place. During 9–11 September 1985, Handsworth, an area to the north-west of Birmingham, experienced widespread protests and street violence. In this post, we’ll look at the context for that Autumn and see how the chronology overlaps.

Continue reading “Part 2 – Rehearsals and Riots, a chronology”Staging race, protest, justice and revolution in Thatcher’s Britain: Les Misérables and the autumn of 1985

I’ve been sitting on this academic article for a couple of years – I meant to come back and edit it and revise it, but decided that ultimately I wanted it to exist. As ever, I’m writing from the position of a white British academic in making these arguments. It explores the relationship in much further detail and thinks about how whiteness is coded into what we experience in megamusicals. Because it’s written in the ‘before-times’ – it doesn’t mention the most recent summer of protest. Also, academic articles are generally massive – I’ve posted it as a series of blog posts and slightly edited it so it works on a blog series rather than an individual piece.

Part 1: Staging race, protest, justice and revolution

Part 2: Rehearsals and Riots- a chronology

Part 3: Handsworth Songs

Part 4: Staging Revolution in Handsworth Songs

Part 5: Les Mis, white optimism, and Autumn 1985

Part 6: The Megamusical and Whiteness

Part 7: White Women in Les Mis – a sense of an ending

Continue reading “Staging race, protest, justice and revolution in Thatcher’s Britain: Les Misérables and the autumn of 1985”Tracing the history of Hulme Hippodrome

Save the Hulme Hippodrome campaign (https://niamos.co.uk/savethehippodrome) is raising funds to save the theatre from developers (https://www.crowdfunder.co.uk/save-hulme-hippo). The theatre has an important place in British theatre history, as a surviving venue in the variety theatre networks that dominated British theatre from 1900 to the 1950s. In this article, I explore some of the performers who worked at this beautiful and at-risk theatre.

Embed from Getty Images Continue reading “Tracing the history of Hulme Hippodrome”