This summer Avril Coleridge-Taylor’s music will be played at the Proms for only the second time, with her piece ‘The Shepherd’ receiving its debut as part of the Great British Works Prom on the 4th August. She is a recent Proms arrival, her orchestral work ‘A Sussex Landscape’ was first performed there only last year. Yet despite this long neglect of her output, Avril was no stranger to the Albert Hall as a venue for her own work (and yes, the Proms only moved to the RAH in 1941). The Coleridge-Taylor family had a special connection with the concert hall.

Continue reading “Avril Coleridge-Taylor and the Royal Albert Hall”Category: Black History

Program Notes for Avril Coleridge-Taylor’s ‘Comet Prelude’

This is a copy of a programme note I wrote for Croydon Music and Art’s recent performance of this extraordinary piece. I’ve added some images to the story so you can see a little more! It was written to help children and young people understand more of the context about the music they were playing.

Avril Coleridge-Taylor was born in South Norwood in 1903 and lived in 66 Waddon New Road in Croydon. She was the daughter of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, the famous Black British composer, and so she grew up in a house of music: he was a successful composer and conductor not only in London’s music scene but around the world. This happiness was very brief, aged just 9, Avril experienced the tragic and very public loss of her Dad, who died from pneumonia aged only 37. She spent much of the rest of her life navigating his legacy and fighting to preserve it, while building her own career as a composer and a conductor.

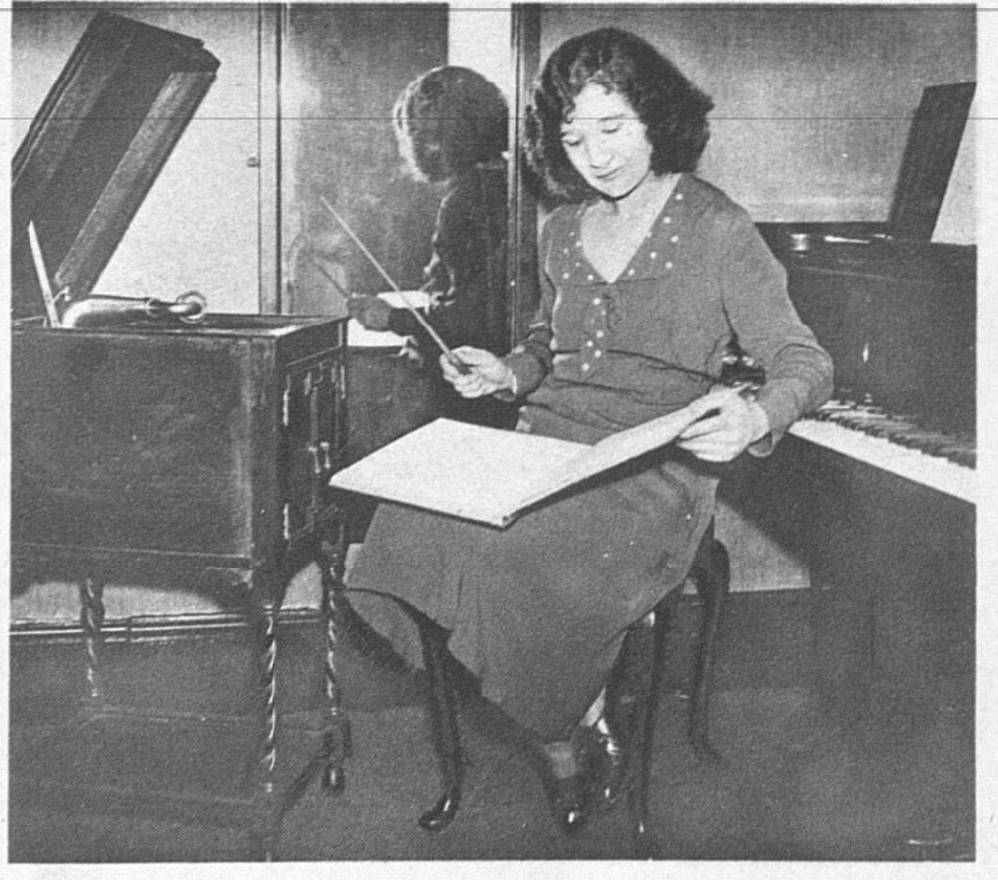

She began composing at 12, and over her lifetime produced an array of music – some of which under the name of a man – much of which has been unperformed. She conducted at the Royal Albert Hall when she was 30 and formed the Coleridge-Taylor Symphony Orchestra in 1941. With her brother she worked hard to secure her dad’s legacy: while successful in his life, his impact began to be forgotten. It’s only in recent years his full musical contribution has been reassessed, and with that, Avril’s herself.

This piece, the Comet Prelude, was written at least partly on board a plane in 1952 – Avril was a passenger on the first ever jet flight, the De Havilland Comet, which would carry regular commercial passengers from London Heathrow to Johannesburg, South Africa. The beginning of the jet age was a time of great excitement about being able to reach far off destinations. It seems like she was brought onto the flight especially to compose while on board the plane – to show how thrilling air travel be. The plane stopped at several destinations to refuel including Rome, Beirut and Khartoum, stops which influenced her writing of the score.

Avril was going to Cape Town to conduct for the South African Broadcasting Company, something which at the time in the country was limited to white people. This was because of a policy that enforced the racist separation of people to give white people the most power, a system called Apartheid. Though she performed in South Africa for two years, when the South African government realised that Avril had a Black father and a white mother, her bookings were cancelled.

Understanding Avril and what she was doing in South Africa isn’t straightforward, and it is difficult to draw clear conclusions about it. [NB. Leah Broad and Samantha Ege have a fascinating piece on this here] Some have suggested she wanted to pass as white in order to change the government’s opinions, others that she wanted to build a career she wasn’t able to have in the UK due to sexism. We just don’t know, but what we do know is that the experience changed her, and she went on to support many other Black musicians in her later career, for example, she formed and led a choir of performers of colour in the UK in 1956. It’s worth remembering she was a composer and a conductor, and that she wrote this piece to conduct it.

Eva Jessye

(b. 1895, Coffeyville, Kansas – 1992)

Choir director, music director, activist, composer, journalist. Led the official choir of the March on Washington (1963)

Jessye’s musical leadership during the 1920s and 1930s placed her at the helm of some of the most important significant productions during this period, on Broadway and in Hollywood. She was a music director for King Vidor’s Hallelujah (1929), the first Black cast sound film (though Vidor was white), and her choir, the Dixie Jubilee Singers appeared in the film. She was accepted to university aged 14, because she wasn’t allowed to enroll in high school education as a Black woman. She met and was inspired by Will Marion Cook, and after graduation worked as a high school teacher. In this article I’ve found some of her remarks in interviews and coverage of her work.

Continue reading “Eva Jessye”Margaret Rosezarian Harris

Margaret Harris (1943 – 2000) is slightly better remembered for her work as a conductor than her contemporary, Joyce Brown. She had a long association with the musical Hair and conducted over 800 performances, on Broadway and as MD for its national tours .

There’s much more to Harris’s career, and retracing newspaper coverage of her work reveals interviews with her, and the prospect of several Broadway shows she was never credited for. Footage of Harris conducting and playing the piano has also been found, and shared here for the first time.

Continue reading “Margaret Rosezarian Harris”‘I have a reservoir that hasn’t been tapped’: uncovering the groundbreaking work of Joyce Brown

Joyce Brown (1920 – 2015) – is regarded as both the first Black woman to conduct any Broadway show (in 1965) and to open a new show as conductor (1971). Her contribution was phenomenal: to music and music education; to building up Black community on Broadway; and to making opportunities for Black musicians at every stage of their career was phenomenal. Yet when she died in 2015, there was no obituary that recounted her achievements on the pages of a national newspaper. To date, she has no Wikipedia page, and Google turns up only a few articles that lay out her achievements.

This article builds on the little that is known about her by searching through digitised newspaper records of her work. It lays out Brown’s career alongside her own words, retraced from the many interviews she did during her career.

Continue reading “‘I have a reservoir that hasn’t been tapped’: uncovering the groundbreaking work of Joyce Brown”