This summer Avril Coleridge-Taylor’s music will be played at the Proms for only the second time, with her piece ‘The Shepherd’ receiving its debut as part of the Great British Works Prom on the 4th August. She is a recent Proms arrival, her orchestral work ‘A Sussex Landscape’ was first performed there only last year. Yet despite this long neglect of her output, Avril was no stranger to the Albert Hall as a venue for her own work (and yes, the Proms only moved to the RAH in 1941). The Coleridge-Taylor family had a special connection with the concert hall.

If Samuel Coleridge-Taylor was at the centre of British musical life, Avril found a way to find a position close to it, during a period when she was facing immense barriers as a woman of Colour and as a woman. (Since I’m talking about both father and daughter, I’ve taken the slightly unusual step of referring to them both by first name in this post. And as you might expect for music making in South Kensington, quite a lot of the institutions in the story have Royal at the front of them).

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s ‘Hiawatha’ at RAH

Samuel’s choral masterpiece ‘Hiawatha’ is now rarely performed – and if it is, only in sections – not least because of the complexities it presents a modern audience. The work is a setting of US writer Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1855 poem of the same name, a poem which has its own complex legacy in what the impact of its representation of indigenous and first nation cultures has been:

Longfellow brought positive attention to the Ojibwe people and helped spur the preservation of some elements of their culture. However, he also Europeanized their legends and assimilated their culture into the American mainstream. Because of this, Hiawatha has a complicated legacy that has impacted perceptions of Native Americans in this country for over 165 years. NPS.gov

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s setting of Hiawatha was partially premiered at the Royal College of Music in 1898 where he was then a student. Only two years afterwards, it was performed over the road at the Royal Albert Hall, although still as incomplete excerpts. That performance featured the Hall’s resident choir the Royal Choral Society, and conducted by Samuel himself. It had its full premiere as a complete work in 1901, again at the Royal Albert Hall, conducted by Frederick Bridge.

The Hiawatha performances are a complicated mixture of cultural admiration threaded with cultural appropriation. Thousands of amateur singers took part in these performances over the years, over 1,000 alone in 1930. Singers often used what would now be called ‘redface’, stereotypical and racially caricatured representations of indigenous peoples. At the same time, indigenous performers were sometimes included in the casting: baritone singer and spiritual leader Os-Ke-Non-Ton, chief of the Kanien’kehá:ka nation (Mohawk), performed in the pieces from 1929 onwards. Tessie Mobley, from the Chickasaw Nation, performed under her chosen name of Lushanya.

The following year, Bridge conducted the London premiere of another cantata by Samuel, ‘The Blind Girl of Castél-Cuillé, Op.43′ which had been composed for the Leeds Music Festival. Like ‘Hiawatha’, the piece was a setting of a Longfellow poem, (it is hard to imagine how either piece could be performed today, surely only with substantial re-working of both librettos).

In 1904, Samuel conducted another major work, again with the Royal Choral Society as chorus, the London premiere of his large scale choral piece, ‘The Atonement – A Sacred Cantata’, in 1904. A piece, which thanks to the work of Bryan Anthony Ljames in editing the score, is being performed this summer (2025) at the Three Choirs Festival at Hereford Cathedral.

Many more performances took place of Samuel’s work at the Hall before his untimely death in 1912, shortly afterwards there was a memorial concert to raise money for his widow and family. The financial difficulties he faced seem hard to align with the phenomenal success that Hiawatha had, in fact, Samuel had sold the copyright for the piece for 15 guineas, and benefitted little from its popularity.

After Samuel’s death Royal Choral Society continued their connection with Hiawatha in annual performances from 1913 to 1926, largely conducted by Sir Frederick Bridge and in later years Henry Balfour Gardiner and Eugene Goossens. That the performances continued during the First World War speaks to their status by that point. In 1924, Hiawatha Coleridge-Taylor, Samuel’s son, conducted the ballet excerpt at one annual performance. Avril went on to perform in one of these huge productions as a ballet dancer in 1933 (Acton Gazette, 4 August 1933, 5)

From 1925, Malcolm Sargent took up what became a nearly life long connection with its performance, it was performed annually from 1928-1939, and even during the war at Albert Hall in 1941, 43, 44 and 45. Sargent conducted the last RCS performance in 1964.

Avril Coleridge-Taylor and Albert Hall

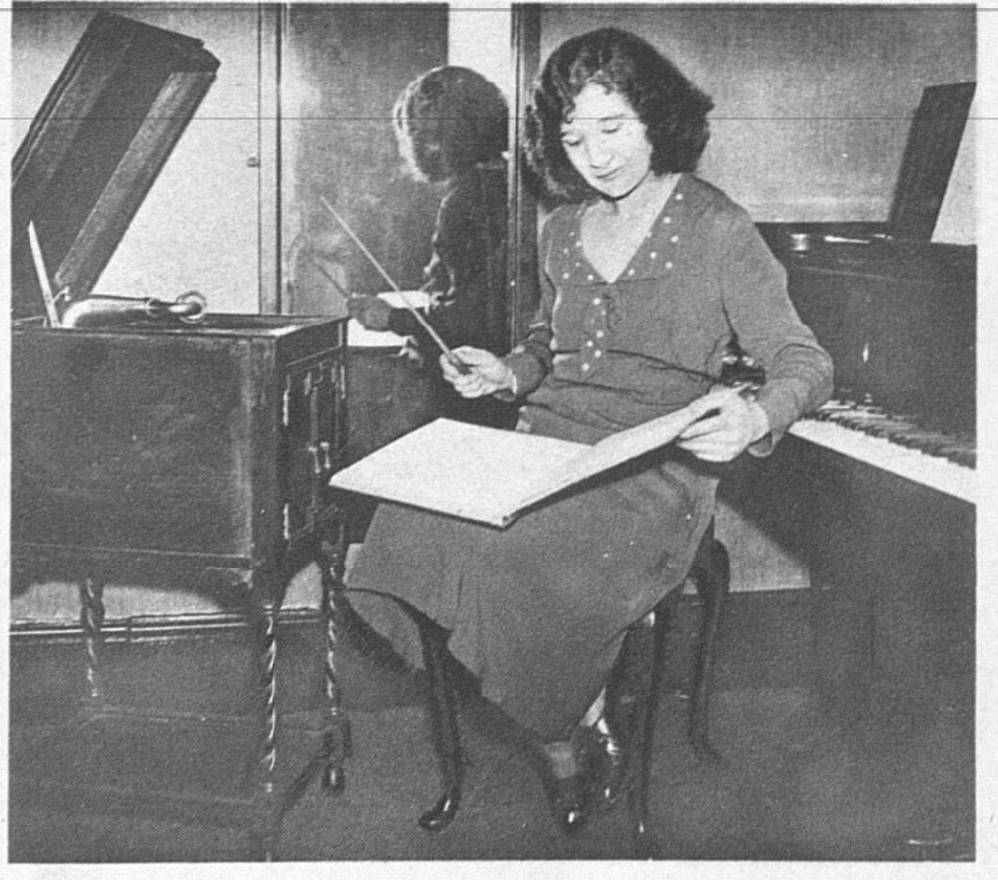

By the time Avril’s career intersected with the Albert Hall, she had already made headlines in 1932 for being the second woman to conduct the Royal Marines band (Dame Ethel Smyth being the first). The following year, she conducted her own music at the Albert Hall for the first time with the orchestra she founded, in ‘Poem for Orchestra’ – ‘To April’, as part of the [Lily] Payling subscription concerts. As part of that concert she also conducted her father’s ‘Othello suite’. This single example typifies the work Avril carried out, of navigating her own career while caring for her father’s artistic legacy. She conducted the BBC Orchestra playing her fathers music in 1942

She would return to the Albert Hall in April 1948, when she conducted a charity performance of ‘Hiawatha’. The concert, in aid of United Jewish Relief Agencies, was again with the Coleridge-Taylor Symphony Orchestra (and was repeated later that year.) She conducted again there in January 1950, in a ‘concert in aid of the Wireless for the Bedridden Society’.

She was consistently employed as a conductor, overcoming considerable the intersectional oppressions and barriers she experience during her lifetime. And there is one further crossover, her connection to Malcolm Sargent, who had been so important in the prolonged performance history of her father’s best known work at the Albert Hall. After his death in 1967, Avril formed and conducted ’The Malcolm Sargent Symphony Orchestra’ in the early 1970s, across the UK.